Wild Ride

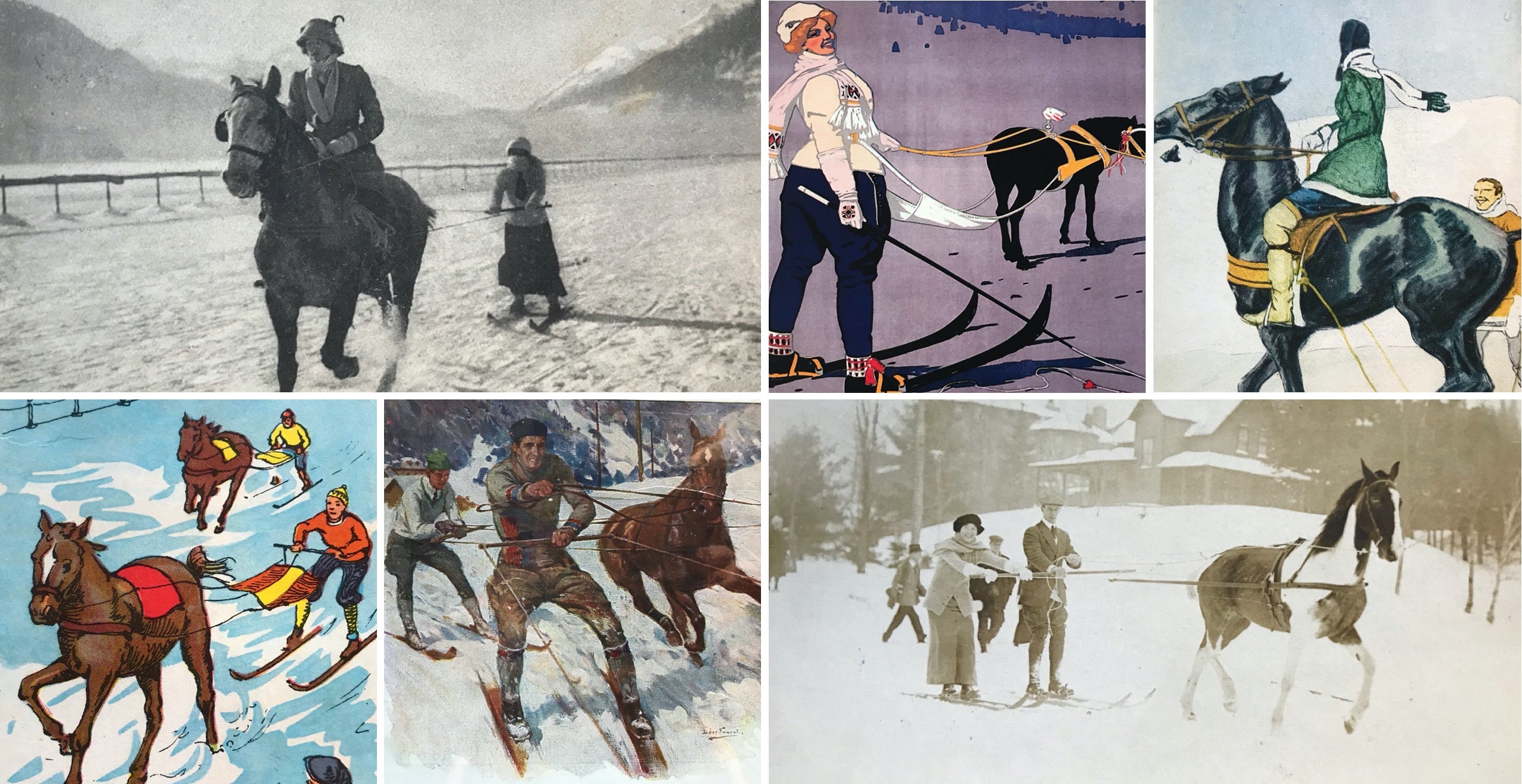

The quirky, long-forgotten sport of skijoring gets a 21st century makeover in the mountains of the American WestThere are varying accounts as to exactly when the sport we now know as skijoring came to be, but at some point at the end of the 18th century, one skier in St. Moritz had a bold idea: to be pulled along by a horse. “It began with hotel guests, mostly women, being pulled through the village by mounted horses” Alfredo “Lupo” Wolf explains on a call from his home base in Switzerland. A skiing and skijoring veteran, Wolf is now the go-to instructor for guests of the Kulm Hotel, located in St. Moritz, and an ardent keeper of skijoring history.

It wasn’t until 1906 that skijoring began to blossom into a truly competitive sport, thanks to a group of locals who devised a journey from downtown St. Moritz to the neighboring village, Champfèr, and back, a roughly 2- mile journey. “It took 20 minutes and 22 seconds, and the winning horse was called Blitz,” Wolf adds. From then on, the small yet glitzy alpine village became synonymous with skijoring, introducing group races in 1907 on the town’s frozen central lake where local legends like Charly Badrutt and Duri Casty earned their stripes. Now, 113 years later, the races still take place three times each year, and skijoring endures as a leisurely activity, sometimes in irreverent, over-the-top variations in which the horse is swapped out for a Ski-Doo or a beautiful vintage car, or perhaps even a helicopter. It all usually ends with an aperitif and a laugh.

There are varying accounts as to exactly when the sport we now know as skijoring came to be, but at some point at the end of the 18th century, one skier in St. Moritz had a bold idea: to be pulled along by a horse. “It began with hotel guests, mostly women, being pulled through the village by mounted horses” Alfredo “Lupo” Wolf explains on a call from his home base in Switzerland. A skiing and skijoring veteran, Wolf is now the go-to instructor for guests of the Kulm Hotel, located in St. Moritz, and an ardent keeper of skijoring history.

It wasn’t until 1906 that skijoring began to blossom into a truly competitive sport, thanks to a group of locals who devised a journey from downtown St. Moritz to the neighboring village, Champfèr, and back, a roughly 2- mile journey. “It took 20 minutes and 22 seconds, and the winning horse was called Blitz,” Wolf adds. From then on, the small yet glitzy alpine village became synonymous with skijoring, introducing group races in 1907 on the town’s frozen central lake where local legends like Charly Badrutt and Duri Casty earned their stripes. Now, 113 years later, the races still take place three times each year, and skijoring endures as a leisurely activity, sometimes in irreverent, over-the-top variations in which the horse is swapped out for a Ski-Doo or a beautiful vintage car, or perhaps even a helicopter. It all usually ends with an aperitif and a laugh.

There are varying accounts as to exactly when the sport we now know as skijoring came to be, but at some point at the end of the 18th century, one skier in St. Moritz had a bold idea: to be pulled along by a horse. “It began with hotel guests, mostly women, being pulled through the village by mounted horses” Alfredo “Lupo” Wolf explains on a call from his home base in Switzerland. A skiing and skijoring veteran, Wolf is now the go-to instructor for guests of the Kulm Hotel, located in St. Moritz, and an ardent keeper of skijoring history.

It wasn’t until 1906 that skijoring began to blossom into a truly competitive sport, thanks to a group of locals who devised a journey from downtown St. Moritz to the neighboring village, Champfèr, and back, a roughly 2- mile journey. “It took 20 minutes and 22 seconds, and the winning horse was called Blitz,” Wolf adds. From then on, the small yet glitzy alpine village became synonymous with skijoring, introducing group races in 1907 on the town’s frozen central lake where local legends like Charly Badrutt and Duri Casty earned their stripes. Now, 113 years later, the races still take place three times each year, and skijoring endures as a leisurely activity, sometimes in irreverent, over-the-top variations in which the horse is swapped out for a Ski-Doo or a beautiful vintage car, or perhaps even a helicopter. It all usually ends with an aperitif and a laugh.

It’s existed on US soil in varied forms, too, rumored to have originally found its way overseas when soldiers from the 10th Mountain Division, stationed in the Alps, returned home from World War II. It wasn’t until the 1980s, though, that skijoring in the US transformed, and rose to the level in which it exists today. No longer does the horse gallop along with a disarming gait, or even carry racers along in a straight line. Instead, it’s all done at death-defying speeds, around hairpin turns, over ramps, through a course of slalom gates, and across the finish line, usually all in less than 30 seconds and at speeds of up to 25 mph—all with a healthy dose of the American West. “When I went to St. Moritz about five years ago, the Swiss had no idea that we were competing in the United States, and that we were doing it in a very different way,” Loren Zhimanskova, head of nonprofit organization Skijor International, tells us. “They thought we were crazy, because we have cowboys on the horse and we’re setting an obstacle course, versus just racing around a track together.”

And while it’s a thrill to witness as a spectator, the true rush comes when you clip into a pair of skis, as one of the country’s top skijoring competitors, Tyler Smedsrud, can attest. “Even after doing it for so many years, it’s still crazy how anxious you get leading up to the event and how much the nerves build, even though you’ve done it so many times,” Smedsrud, who lives in Ouray, Colorado, says. “It’s tough to put into words the adrenaline rush and the addiction, but I’ve definitely gotten hooked on it.”

A seasoned skier, Smedsrud was introduced to skijoring on a whim by a friend shortly after graduating from Montana State University. “I grew up ski racing, so making the gates and going off the jumps and all that wasn’t a problem for me,” he recalls. “Handling the rope was the difficult part. You’ve got to be moving up and down the rope depending on if you’ve got to make a gate. Sometimes the horse is cutting to the left, and you’re going to the right, so you’ve got to let rope out. If you don’t climb back up on the rope after that gate, then eventually you’re going to run out of rope, and once you’re at the end of that rope, then you’re done.”

More than a decade later, Smedsrud has honed his craft, learning who his favorite riding partners and horses are, including a speckled white mare named Derby, ridden by teammate Sarah McConnell. “Derby is always giving you the wide eye in the starting line, like she’s saying, ‘Don’t mess this up,’” he says. “It seems like she wants to win more than Sarah and I want to win.” Together, they compete in the small circuit of races in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Red Lodge, Montana, where the national finals competition takes place every March. Organized by Kristen Beck and Monica Plecker and known as the longest-running annual skijoring race, it’s the culmination of its three-month season, and a chance for the community to celebrate this niche sport that has taken on new life in recent years.

A seasoned skier, Smedsrud was introduced to skijoring on a whim by a friend shortly after graduating from Montana State University. “I grew up ski racing, so making the gates and going off the jumps and all that wasn’t a problem for me,” he recalls. “Handling the rope was the difficult part. You’ve got to be moving up and down the rope depending on if you’ve got to make a gate. Sometimes the horse is cutting to the left, and you’re going to the right, so you’ve got to let rope out. If you don’t climb back up on the rope after that gate, then eventually you’re going to run out of rope, and once you’re at the end of that rope, then you’re done.”

More than a decade later, Smedsrud has honed his craft, learning who his favorite riding partners and horses are, including a speckled white mare named Derby, ridden by teammate Sarah McConnell. “Derby is always giving you the wide eye in the starting line, like she’s saying, ‘Don’t mess this up,’” he says. “It seems like she wants to win more than Sarah and I want to win.” Together, they compete in the small circuit of races in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Red Lodge, Montana, where the national finals competition takes place every March. Organized by Kristen Beck and Monica Plecker and known as the longest-running annual skijoring race, it’s the culmination of its three-month season, and a chance for the community to celebrate this niche sport that has taken on new life in recent years.

A seasoned skier, Smedsrud was introduced to skijoring on a whim by a friend shortly after graduating from Montana State University. “I grew up ski racing, so making the gates and going off the jumps and all that wasn’t a problem for me,” he recalls. “Handling the rope was the difficult part. You’ve got to be moving up and down the rope depending on if you’ve got to make a gate. Sometimes the horse is cutting to the left, and you’re going to the right, so you’ve got to let rope out. If you don’t climb back up on the rope after that gate, then eventually you’re going to run out of rope, and once you’re at the end of that rope, then you’re done.”

More than a decade later, Smedsrud has honed his craft, learning who his favorite riding partners and horses are, including a speckled white mare named Derby, ridden by teammate Sarah McConnell. “Derby is always giving you the wide eye in the starting line, like she’s saying, ‘Don’t mess this up,’” he says. “It seems like she wants to win more than Sarah and I want to win.” Together, they compete in the small circuit of races in Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, Utah, and Red Lodge, Montana, where the national finals competition takes place every March. Organized by Kristen Beck and Monica Plecker and known as the longest-running annual skijoring race, it’s the culmination of its three-month season, and a chance for the community to celebrate this niche sport that has taken on new life in recent years.

“It’s really this amazing combination of cowboys and extreme skiing,” Plecker told us of the race, which takes place against a jaw-dropping mountain vista of the Beartooth Mountain range. In addition to leading the production of the event, both she and Beck find time to join as mounted riders. “You let the horse go, and it is just the most exhilarating, fun thing in the world, because you’ve got three heartbeats working together at one time to master this course.”

This teamwork, and the fact that skijoring requires such an atypical melding of unique, time-honored skills, is what sets it apart from the average winter attraction. Thus, it continues to grow in popularity for both spectators and participants, leading some, like Zhimanskova, to lobby for the sport’s inclusion in the 2026 or 2030 Winter Olympic Games. “The growth of the sport in the last decade has been unprecedented in terms of exposure,” she says. “We have momentum, and I’ve seen many facets of the sport that can certainly go forward in a lot of ways—the Olympic angle is just one of those.”

- Courtesy of Getty Images

- Courtesy of Loren Zhimanskova